As a web developer turned Salesforce developer I learned some things along the way about how the web works. I realized recently some of the important details aren’t common knowledge among Salesforce developers. In part because Salesforce developers do not think of themselves as web developers.

Salesforce is web application. It’s one of the most popular and complex single page applications (SPA) in existence. If you have spent a time as an Apex developer, or Salesforce was your first platform for writing web applications, you might not think about it that way.

But if you are a Salesforce developer, and you are creating LWCs – you are a web developer. Even a Salesforce administrator embedding web forms on your Experience Cloud side benefits from knowing how web developers think.

So let’s take a few minutes to go over important things web developers must know to survive.

Trust Nothing!

The first rule all web developers have to learn is to trust nothing. Every single piece of data you get in your web application is suspect. In Apex and Flows, Salesforce provides you a lot of security checking and input validation. That lets you trust data types, who the running user is, and all kinds of other useful things. But if you are writing an LWC, or dealing with guest user input, you’re missing some or all of that validation.

If you are doing anything with the data without that validation – you have to do it. That includes anything coming back from the JavaScript controller in an LWC. It also includes anything that was validated in JavaScript on your form or component. You have to assume that no browser-side validations were run, and that everyone is always attempting to reach data they shouldn’t see.

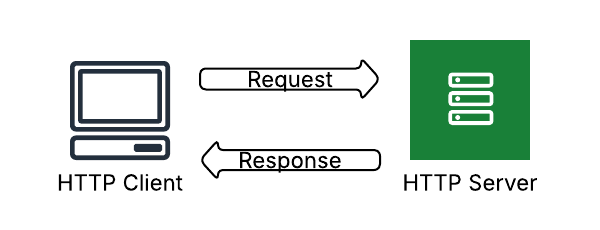

HTTP Basics

Everything coming and going from Salesforce travels over Hyper Text Transfer Protocol (HTTP). HTTP is a stateless application protocol meant for moving documents between servers and clients. The web browser is the client everyone thinks about – but that’s just one potential client. Any piece of software that can follow the rules of HTTP can connect to Salesforce.

The connections are stateless, each time the client connects the server only knows what’s included in the current request. On the Salesforce side that means they have no way to actually know what happened on the client side. That client could be a web browser following all of the rules. It could be a tool like Postman or Bruno and only exchange raw data It could also be a custom piece of software maliciously looking like a web browser but doing it’s own thing.

For all the sophistication of the web, and all the various APIs that run on top of HTTP, it’s actually a pretty simple protocol. All the really cool stuff is what we do on top of it. There were two great insights in its creation:

- Have simple set of rules that everyone can follow.

- Keep it free to implement and use so that people would follow it.

For each request the client (your web browser) sends a message to an address. The request could just be to get a specific document or resource (the R from URL), or it could also include a bunch of additional data – like cookies or any collection of data you want to send to the server. The server uses that request to decide what to send back. But for any given request the server only knows what the client told it – at least about the request and the client. The server passes that data to an application that looks at the data, and using what it already knows tells the server how to respond.

The server (or really the application behind it) has a number of choices: it can send you the resource you requested, tell you to look some place else, perform some action and confirm it succeeded for failed, or it can send several kinds of errors (or it can declare itself a teapot).

The final step is for the client to show the user what came back. We think of that as a web page (although that’s usually a collection of hundreds of requests), but this step is optional – the client does whatever it was built to do with the data it got back. It can send another request that looks like someone doing something that’s really just the next load of data they want the server to process.

How We Track State: Cookies

If HTTP is stateless, how does Salesforce know who is making a request to enforce security? Cookies.

Privacy advocates have given Cookies a bad name – some of that is deserved – but they are a critical part of keeping any web application secure. Cookies are just a small block of text, a key-value pair, that travel as part of requests and responses over HTTP. They are neither good nor evil, they are just text. What matters is what we do with that text. Because they can go back and forth on any request they are useful for sending session information to allow the server to track state.

Cookies should be used to save two kinds of things: a reference to something on the server, data to be used by the client.

The reference to something on the server is typically the session cookie. The session is how we track who is logged into an application. That session itself needs to be on the server, but the ID of the session goes back and forth in each request. Salesforce knows that session 1234 (the Ids is much harder to guess) is me doing work, but my browser only knows that my session Id is 1234. Session Ids are meant to be unguessable during attacks, so the only way to steal my session is to get that Id from me. Stealing those Ids used to be easy, that’s why nearly the entire web is encrypted now.

The server should trust nothing it gets from the client. To check even a session the application should validate other data points to try make sure the session hasn’t been stolen (e.g. validating the same browser and operating system in use). But remember all those data points can be faked. The server only knows what the client tells it, so it can be lying about everything. Even the IP address a request came in from, and the response should go back to, can change and may not match anything related to the actual device in use.

So while Cookies allow a server to track state, and know who made a request (usually), all the other data coming in needs to be sanitized, validated, and generally handled with care.

Data, Parameters, and Logging

When designing applications for the web it’s important to keep track of how data will be sent from the client to the server and what the server will log. For example: GET requests typically put most of their data into the URI of the request itself. It can either be part of the path /request/path/with/values/1234 or in URL parameters: /request/path/parameters?value=1234. That’s not a problem, except that request URI’s get logged by most servers in plain text. So you don’t want anything sensitive in the path or parameters. Putting the user name and password, session Id, and similar things into the URI is extremely bad /request?user=aaron&password=neverDoThis

POST, PATCH, and PUT requests all expect data into be part of the main body of the payload (this is also possible with GET but rarely done). That content is not logged by the HTTP server, it’s processed by the application – which is typically what we want.

Why This Matters to Salesforce Developers

In most of our work on Salesforce, particularly when we are writing Apex or Flows, Salesforce abstracts all of this away for us. But when we are working with the guest user (anonymous end points), or embedded forms, it’s important to understand what’s happening under the hood because Salesforce’s ability to protect us is limited.

In the case of a form that can be sent anonymously, the client sending the form data is likely sending a POST request with some, or all, of the fields on the form. There is no reason that POST needs to follow a GET request for the form. There is no reason the client has to run JavaScript-based validations. There is no reason to believe any of those things happened while processing the form data. Salesforce still provides what protections it can to avoid their system doing bad things with data in future display of the data. But unless you have Salesforce-side validations you cannot assume validations that ran in your LWC actually ran against the data you were sent. You can’t assume JavaScript ran at all. You can’t assume a human was sitting in front of the client. Every piece of data coming in must be treated as suspect.

As Salesforce developers we are used to assuming Salesforce handled all of the validations for us – because they do when handling a regular record update through a regular page. But once you take over handling parts of that interaction in your LWC you took on responsibility for considering what happens if a bad actor posts data to your org without the actual JavaScript running. The chances that’ll happen with a typical in-house user are small for most orgs. The chances that’ll happen on an authenticated Experience Cloud site are larger, but still reasonably small. The chances that’ll happen with the guess user are huge.