I’ve been struggling with what to write about our new president, the protests he’s triggered, the ban on refugees he’s ordered, the families he’s dividing, the hateful things he has said about many groups, and all the related news. While this is mostly a technology blog and much more articulate people are already saying things worth hearing, these are not events I can allow to pass without comment.

For a variety of reasons I haven’t been able to attend the protests, except I accidentally attended part of a rally in Philadelphia (I thought the rally pictured above was over when I met a friend for dinner right in the middle of it), but it’s been exciting to watch the sustained energy the last few weeks.

Last week my wife paraphrased some of the memes that have been going around: Remember all those times in history class you thought “If I had been alive during ____ I would have ____”? What you are doing now is exactly what you would have done then.

She didn’t mean it as a direct challenge to me, but I haven’t been able to let it go. In part because while I’ve had good answers in the past, I’m not sure I have a good answer at the moment. Besides, the challenge takes on another level of importance when coming from a historian.

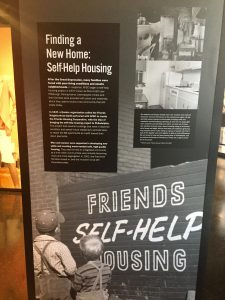

While I was in Philly I visited American Friends Service Committee’s Waging Peace exhibit marking their 100th year.

For four generations my family has spent time working and volunteering for AFSC, and there were markers of some of our work in the exhibit. Our widely different roles matched the times and events we were living through. As young adults my great grandparents worked in post-World War I Germany and France, and my great-grandfather later led the construction of a housing co-op. My grandfather and father served as conscience objector with AFSC during World War II and Vietnam. Most of my father’s siblings and their children have volunteered in various ways with some AFSC program or another, often packing donated clothing in the basement of Friends Center in Philadelphia. I spent ten years working in the IT and Communications departments in Philadelphia.

My great grandparents there was little formal training or planning. They both took on roles I can barely imagine doing now, let alone doing them at 22 in countries destroyed by war. Later in his life my great grandfather described part of his work after the armistice:

I was sent with an English boy to Bethlainville, near Verdun, none of the now returned owners knew who we were or why we were there. “To plow our land? Oh no! Americans come to take our land away from us?” My two high school years of French were put to a real test. We are here for Love. We are not the Americans you have met with during the war. We want no pay. But one young girl who had lost both her father and brothers, completely alone, said she would take a chance. “Oh but you’ll be raped said the others” O.K. she will have a gamble. So Jacoby plowed from day break until noon and then I plowed from noon until I couldn’t see at dark. Land all plowed, now we will see what these young men really want. Nothing? Nothing but love. Not the kind she expected. From then on everybody wanted their land plowed. Later on another crew of Americans came with seeds, tools, clothing, etc. So the people of Bethlainville were restored to almost normal living.

Relief work has grown a bit more formal in the last century.

He later returned to AFSC to support the self-help housing program, first in Ohio, and then leading the program in north Philadelphia which renovated a building to create a co-op that still functions today; my cousin, his wife, and daughter are members of the co-op.

My own work at AFSC was much less exciting: I sat in relatively comfortable offices and made sure the technology needed to support the programs worked. I supported mostly communications, and fundraising, and my program involvement tended to be limited to supporting their public facing functions. I was in entirely administrative roles: I was overhead.

Now I easily see what I couldn’t always see then: the value I contributed over 10 years. Too often we denigrate administrative functions at nonprofits as wasteful distractions from their true mission. But the truth is that well done administration is critical to the success of any good organization. They need money to pay the staff, they need web sites to inform people about their work, they advocate for systemic change, they post pictures of their own pets to grab your attention so you will help their work.

Now I’m struggling to find ways to help as the world seems to spin out of control and the US government does things even worse than we did while I was at AFSC (the US went to war twice, admitted torturing people, and openly spied on citizens, so this is a fairly high bar to cross).

While I’ve been pleased, and frankly surprised, at how effective the current protests appear to be, I believe over the next four years the resistance the administration’s fermentation of hatred and distrust will have to be a community by community movement. The lack of trust between communities, and the lack of political power make sustained broad-based movements hard to imagine. There are communities under new attack, and others that have been under assault for decades now starting to find their voices: many are voices of pain and anger. Even as we see mass protests we also see infighting within them and outside resistance from communities with shared interests.

I’ve written in the past about my sister-in-law’s students in Maryland. My wife and I posted similar messages to all our personal and social media networks, and hundreds of postcards and letters have poured in from all corners. The teachers read them to the kids, and sent them home so their families also know there are Americans who welcome them. Some of those letters came from other immigrant children, and her students are now writing back to share their warmth and stickers, with the other children. It doesn’t fix everything, but provides some of what that community needs: love, the kind my great grandparents carried to post-war France and Germany.

There need to be people in the world who are willing to go into the most dangerous places, but we can’t all be those people. We also need people working actively in their community to help spread love, respect, and basic dignity.

I’m still struggling to find ways to have a positive, and effective impact, but here are things I’m trying:

- Making hats for a newly arrived Iraqi family I learned about from a woman at church this morning.

- Calling and writing to my elected officials to thank them for the things I think they are doing right and asking them to change what I think they are doing wrong.

- Writing and speaking openly about my concerns.

- Attending rallies when I can, and supporting those who do when I cannot.

- Donating to organizations taking the kinds of action we want to see in the world including Planned Parenthood and likely others (we’re still working on who all that will be).

Please share with me (and others) what you’re doing and what else you think can be done.

I believe that to work for positive change we all need to work in and with marginalized communities and help find positive solutions for their problems – even those expressing their frustration through hate toward others.