Over the last few weeks the US has been moved to action about policing and racial justice in response to the murder of George Floyd. As someone who is deeply concerned about these issues I always struggle to find words I feel do the topic justice; they seem too important to stay silent, too critical to speak about poorly, and too complex for me to write about well. For my limitations in what follows, I’m sorry.

As a society we are still working to understand that the violence and murders by police we see played out regularly in the new is not just the fault of the individual officers or their by-stander colleagues, but also the fault of our society as a whole. This has not happened in a vacuum. Our communities have voted too often for people and policies that brought us here instead of doing something better.

But all those are things you can read about in detail from more skilled writers than me. And if you haven’t you should.

I want to talk here more about the fact that we all know we cannot trust the police to handle complex situations, in particular protests. It is why we all set our expectations that it is simply someone else’s job to maintain calm when large crowds are involved with police.

The most basic sign of this lack of trust is that no one doubts the importance of the long-standing understanding among families raising children of color that they must teach very young kids how to de-escalate with police because they cannot trust officers not to shoot a child playing alone in the park. If that’s not something you’ve known was happening for a long time, I recommend Clint Smith’s letter to his then-future son, and more broadly his recent interview on TED Radio Hour. If you are a person of color, a woman, or mentally ill it’s long been clear that society expects you to protect yourself against police officers.

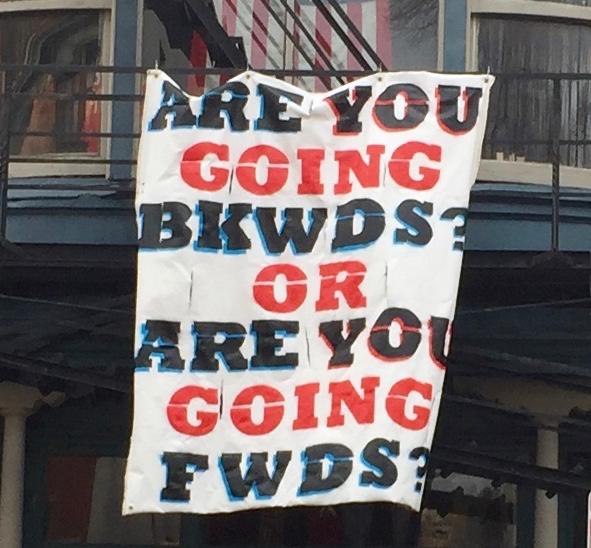

Beyond those seemly obvious, but still debated reasons, we have all long shown we don’t trust police in how we talk about protests. Until the videos of police violence from protests caused a shift in how we talk about these events in the last few weeks we had a very standard story around any riot, protest, or civil unrest which assumed police could not handle angry expressions of the first amendment.

The story starts with a nonviolent march or gathering, and then degrades into a violent riot because of a few bad people in the crowd. The police are be cast as innocent bystanders until the violence broke out, then they became heroes working to regain control for the rest of us. We see these stories on the news and wring our hands about a good message being marred by violence – too bad they didn’t learn Dr. King’s message.

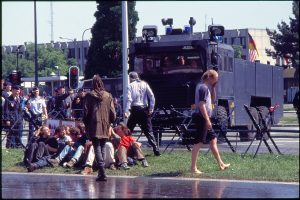

If you have been to a large protest you probably know in your gut that’s not how it works in real life. In practice throughout the day the police are making decisions about how to interact with the crowd. Often this starts with little or no containment during the initial events, then the police start to restrict the group’s movement. They use increasingly aggressive tactics to try to control the physical direction of protesters putting pressure on the crowd they say they want to keep calm. Sometimes they say this is to enforce a permit, sometimes they claim to be protecting businesses, and sometimes they don’t give any reason. When things finally turn angry and violent, the police have made themselves the front line and often starting the actual fighting. There is no actual reason to make this shift in most cases, just things like a sense that protests after dark are more dangerous and the cost of policing.

We have long criticized marchers for damaging small businesses, burning their own neighborhoods, while ignoring that police and politicians tried to control where protests were held and used force to keep people in their neighborhoods.

Reporters, politicians, and police would ignore all the research of large crowd dynamics, and blame the crowd for doing what large groups of angry people do when pressed – fight back.

In the US we started to assume it was the protester’s job to stay nonviolent in the face of extreme police response during the 1960’s and 1970’s when the civil rights and antiwar movements showed it was possible. It is also important to remember that while there were amazing peaceful protests in that period, there were also large riots, rebellions, and general civil unrest. We remember the great example set an inspired few, not the larger contexts of events that unfolded.

Just because we want large protests expressing anger at our government to be nonviolent that does not mean we can reasonably expect every group to manage the needed level of organization and training to make that possible. We have a paid, trained, group of people we already expect to show up for these events – why don’t we assume they are going to help make sure these events are empowering expressions of our first amendment rights? Why do we assume that the unpaid citizens exercising their rights need to be able to handle situations that police cannot?

Currently our police are badly trained at de-escalation, even though it’s been shown to keep them safer. That training will cost money, but we could cover that by cutting funding of unneeded weapons like armored personnel carriers. I know some people who can run that kind of training – trust me they would do a lot of training for the annual maintenance budget on one of those things.

Yes, being a police officer is hard. I agree with the many officers complaining that we expect them to do all kinds of things they shouldn’t be asked to do because yes they need better solutions around them. And of course they should expect they will come home safely at the end of their shifts. But just because a job is hard, and can be dangerous, does not make it okay to do the job badly – in fact that seems like an argument to do the job well.

The flaws in our system are not the fault of individual officers – no one officer can reform the system (although any one of four police officers could have saved George Floyd’s life by stopping his murder). No one mayor, police chief, nor any one person has the power to make the kind of change we need to make our communities safer for everyone in them. Everyone is responsible for their own personal behavior, but dismissing gross misconduct including murders as the acts of a few “bad apples” instead of recognizing that they are part of a system that our society built is an injustice in itself.

The system is well past needing simple reforms being debated in Washington and many state legislatures. Maybe if we’d really reformed things after the police riots of the 1960’s, when departments were smaller and officers less protected from consequences, we could have used incremental measures. Now we need drastic sweeping changes. We need to understand that Camden, NJ’s choice to disband and rebuild their department was a first step that shows you’re serious but doesn’t mean you’ve made enough progress. After you totally reboot you still have to be ready to totally rebuild.