When someone tries to insult you with what you often see as a compliment it is worth stopping to reflect. Am I an activist? If I’m not, should I be?

On Valentines Day this year my wife and I spent a few hours at DSS for a meeting related to some of the children we work with in the Guardian ad Litem program. In the course of a rather tense conversation a caseworker tossed out “Well, I am not an activist.” with the clear intention of implying that I am, and that activists are a problem.

It is the first time I can recall being called an Activist as an insult, and I’ve been a bit hung up on the topic ever since.

Between my personal and professional life I have a very high standard for what it means to be an activist. I have friends, including a former boss, who were arrested the recently protesting the conditions asylum seekers face coming to the US. Among them my friend Lucy who is willing to do this for more than just one cause. I was around when AFSC started to help restore the legacy of Bayard Rustin and his work planning the March on Washington and making the phrase “Speak truth to power” commonly known. My friend Tom Fox traveled around the middle east participating in peace movements until he was kidnapped and murdered in Iraq.

Those are activists.

At AFSC I had colleagues who would argue if you haven’t been arrested for a cause you aren’t really an activist. We had critics who argued that because AFSC staff were paid they couldn’t be true activists. I didn’t then, nor now, fully agree with those arguments, but my point is that when someone calls me an “activist” those are the comparisons they are drawing in my mind.

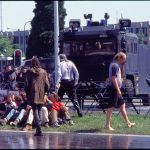

My credentials as an activist on that scale are weak at best. The first time I spent a lot of time with activists was in 1999 during the Hague Appeal for Peace and a peace walk that followed. The group walked from the Peace Palace – home of the international criminal court – in The Hague, Netherlands to Nato Headquarters in Brussels, Belgium. That picture of the water cannon firing on a crowd at the top of the page is mine, although I wasn’t willing to risk arrest that day (my sister was getting married the next week and my mother would have killed me if I’d missed it because I had been arrested in Europe – would a true activist be deterred by such things?).

It was a great experience, but didn’t do a thing toward our goal of nuclear disarmament – I now live in a town supported by nuclear weapons maintenance (and soon pit production too).

After college I took a job at AFSC which consisted of largely back office functions of one type or another – while defining for my career and personally gratifying work there is an important difference between building the tools activists need to communicate and being the activist. In 2008 I was part of planning a peace conference in Philadelphia as part of the Peace and Concerns standing committee, but it is important to note that I objected to the civil disobedience that was part of that event (being a consensus driven process people feared I would block it entirely – but I stood aside so they could move forward).

I’ve been to other events and protests, although sometimes as much accidentally as purposefully. So while the account is not empty, it’s not exactly the kinda stuff that gets you into history books, or even an FBI file worth reading.

Having spent much of my professional life supporting back office functions on nonprofits, and now interacting with DSS as a volunteer who has to be careful about what I share since I have to maintain the privacy of the kids we work with, I struggle to envision myself as an activist. I support activists sure, but I don’t see myself as one.

But when someone tries to insult you with what you often see as a compliment it is worth stopping to reflect. Am I an activist? If I’m not, should I be?

It occurred to me this case worker has a much lower standard of what it means to be an activist than I do – anyone who simply speaks against the status quo in favor of well established laws and precedents are activists in his book. To be fair he’s not far off the suggestion Bayard Rustin, and the committee who helped him write Speak Truth to Power, were making. And as much as I am sure they would deny it, the caseworkers are the most powerful people in the lives of children in foster care: they dictate where the children live, who they can talk to, if/when they see siblings, when they buy clothes, where they go to school, what doctors they see, and without an active advocate they shape how the courts see the children. And right now in South Carolina their power is being tested and reigned in because a group of Guardians ad Litem stood up a few years ago to the rampant systemic abuses.

The ramifications of that class action are still being determined, and no one really knows what the lasting effect will be. But this case worker has inspired me to make sure we honor the sacrifices they made (all were forced to stop fighting for the named children because they were “distractions”).

I’m not sure I am an activist, but I promised those kids I would stay with them until the judge ordered me to stop. No matter what taunting I get from the case workers, their bosses, and others within the power structure I can speak truth to power as long as I must.