I’ve been reading Erik Deitrich’s blog a bunch recently, particularly two pieces he wrote last fall on how developers learn. They are excellent. I recommend them to anyone who thinks they are an expert particularly if you are just starting out.

In short he argues for a category of developer he calls the Expert Beginner. These are people who rose to prominence in their company or community due more to a lack of local competition than raw skill. Developers who think they are great because they are good but have no real benchmarks to compare themselves to and no one calling them out for doing things poorly. These developers not only fail to do good work, but will hold back teams because they will discourage people from trying new paths they don’t understand.

I have one big problem with his argument: he treats Expert Beginning as a finished state. He doesn’t provide a path out of that condition for anyone who has realized they are an expert beginner or that they are working with someone who needs help getting back on track to being an actual expert.

That bothers me because I realized that at times I have been, or certainly been close to being, such expert beginner. When I was first at AFSC, I was the only one doing web development and I lacked feedback from my colleagues about the technical quality of my work. If I said something could be good, it was good because no one could measure it. If I said the code was secure, it was secure because no one knew how to attack it. Fortunately for me, even before we’d developed our slogan about making new mistakes, I had come to realize that I had no idea what I was doing. Attackers certainly could find the security weaknesses even if I couldn’t.

I was talking to a friend about this recently, and I realized part of how we avoided mediocrity at the time was that we were externally focused for our benchmarks. The Iraq Peace Pledge gathered tens of thousands of names and email addresses: a huge number for us. But as we were sweating to build that list, MoveOn ran out and got a million. We weren’t playing on the right order of magnitude to keep pace, and it helped humble us.

I think expert beginnerism is a curable condition. It requires three things: mentoring, training, and pressure to get better.

Being an expert beginner is a mindset, and mindsets can be changed. Deitrich is right that it is a toxic mindset that can cause problems for the whole company but change is possible. If it’s you, a colleague, or a supervisee you have noticed being afflicted with expert beginnerism the good news is it is fixable.

Step 1: Make sure the expert beginner has a mentor.

Everyone needs a mentor, expert beginners need one more than everyone else. A good mentor challenges us to step out of the comfort zone of what we know and see how much there is we don’t understand. Good mentors have our backs when we make mistakes and help us learn to advocate for ourselves.

When I was first in the working world I had an excellent boss who provided me mentoring and guidance because he considered it a fundamental part of his job. AFSC’s former IT Director, Bob Goodman, was an excellent mentor who taught me a great deal (even if I didn’t always admit it at the time). Currently no one person in my life can serve as the central point of reference that he did, but I still need mentoring. So I maintain relationships with several people who have experiences they are willing to share with me. Some of these people own companies, some are developers at other shops, some are at Cyberwoven, and probably none think I look at them as mentors.

I also try to make myself available to my junior colleagues as a mentor whenever I can. I offer advice about programming, careers, and on any other topic they raise. Mentoring is a skill I’m still learning – likely always will be. At times I find it easy, at times it’s hard. But I consider it critical that my workplace has mentors for our junior developers so they continue progress toward excellence.

Step 2: Making sure everyone gets training.

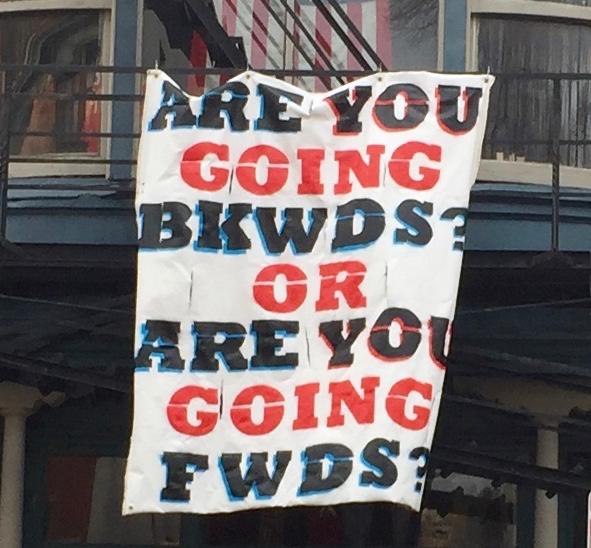

Programming is too big a field for any of us to master all of it. There are things for all of us to learn that someone else already knows. I try to set a standard of constant learning and training. If you are working with, or are, an expert beginner push hard to make sure everyone is getting ongoing training even if they don’t want it. It is critical to the success of any company that everyone be learning all the time. When we stop learning we start moving backward.

Also make sure there are structures for sharing that knowledge. That can take many different shapes: lunch and learns, internal trainings, informal interactions, and many others. Everyone should learn, and everyone should teach.

Step 3: Apply Pressure.

You get to be an expert beginner because you, and the people around you, allow it. To break that mindset you have to push them forward again. Dietrich is right that the toxicity of an expert beginner is the fact that they discourage other people from learning. The other side of that coin is that you can push people into learning by being the model student.

Sometimes this makes other people uncomfortable. It can look arrogant and pushy, but done well (something I’m still mastering) it shows people the advantages of breaking habits and moving forward. This goes best for me is when I find places that other colleagues, particularly expert beginners, can teach me. Expert beginners know things so show them you are willing to learn from what they have to offer as well. They may go out and learn something new just to be able to show off to you again.

Finally, remember this takes time. You have to be patient with people and give them a chance to change mental gears. Expert beginners are used to moving slow but it feels fast to them. By forcing them into the a higher gear you are making them uncomfortable and it will take them time to adjust. Do not let them hold you back while they get up to speed, but don’t give up on them either.