This is the first in a series of posts to break down the questions from my Queries on Queries talk. The full talk is available here.

Are your tools good enough?

Our migrations live and die by our tools.

Are your tools built for the scale of your project? Do they empower you to do your best work or impede rapid progress? Would a new tool serve you better now or in the future?

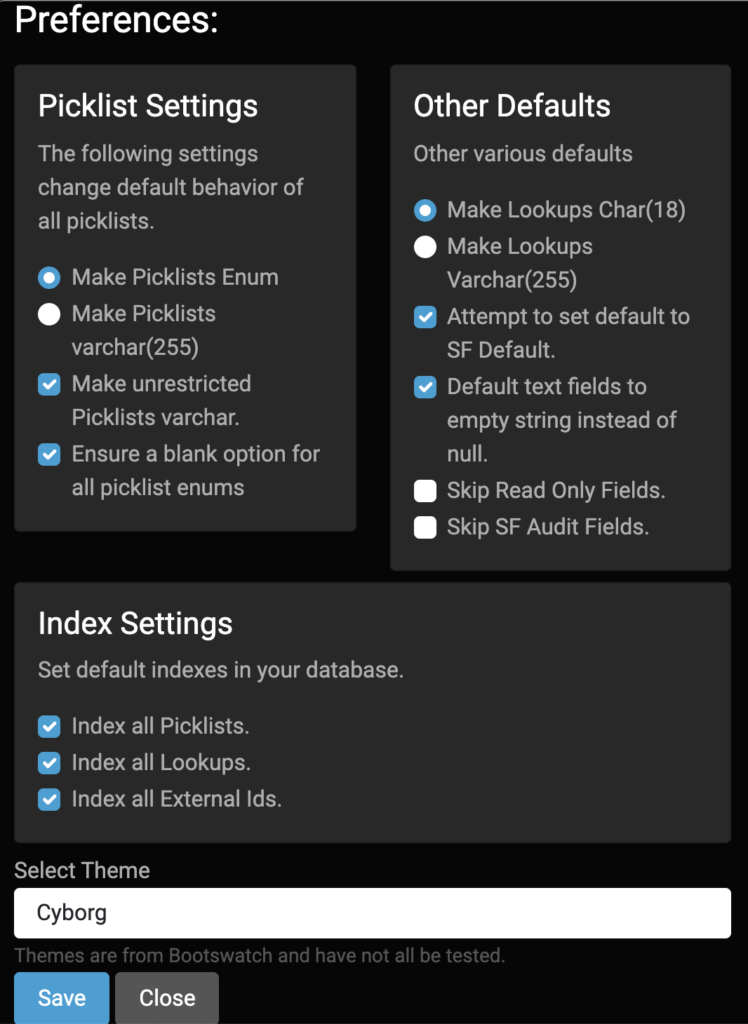

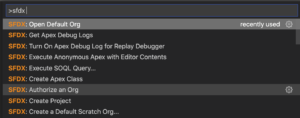

Having the right tools is critical to any job. In data migration we primarily talk about ETLs (Extract, Transform, and Load): tools like Jitterbit, Informatica, Mulesoft, Talend, etc. We also use additional tools to help support the process: a task tracker like Jira, a Data Modeler like Lucidchart, staging database prep like Salesforce2Sql, and more.

It’s easy to say that it’s a poor carpenter who blames his tools, but anyone who has spent time with actual carpenters knows they care a great deal about what tools they use. They might be able to make due with poor tools, but they will do their best work with the right tools for the job.

Each tool you use needs to meet your team’s needs. It should play to your strengths, supports the kinds of projects do you do, and has an eye to the future. A tool that works great for a team of declarative Salesforce consultants might drive developers crazy. A tool that works great for 10’s of thousands of records might struggle with millions; a tool scaled for 10s of millions of records may be overly complex for a project of 30,000.

Make sure you’re using the tools that let you do your best work, now and in the future.

Do you make the data atomic for processing?

Smaller pieces of data are easier to track, manipulate, and test.

Do you divide the source data into its constituent parts? Can you process individual pieces of data easily and cleanly? Can you stop your process after each stage to validate the results?

It can be tempting to process data as it comes: handling whole rows of data in the form they were provided and treating fields as a single data point. In practice exports may have extra rows or columns to deal with related records. Organizations may have encoded multiple points of data into fields like ticket names including a show name, date, and time into the name field. Fields can also contained semi-structured data, like Joomla’s use of arbitrary JSON blobs.

To process this data it is often easier and clearer to extract it from these structures prior to direct processing. It’s not always needed, and rarely required, but doing this clean up of structure – like creating interstitial database tables or predictable data objects – can greatly ease the rest of your job.

Like many problems in software engineering, it’s easier to do good work when you are operating on atomic pieces. Think about the right ways to pull your data into constituent parts when they aren’t there already.

Can you process samples of your data set?

When you have lots of data you need to test small parts to be sure your process works.

Do you know how to create and run small segments of your total input? Are your segments made up of complete and valid samples? Does your sample include all the errors and edge cases your data set will throw at your process?

If you are working with small data sets your sample can be all the data. But when you have a large data set you need to test your process with samples. When you have a multi-step migration you likely need to test the second phase while the first phase is still under construction – again a sample data set is critical.

Having valid test data, that covers all your edge cases, is critical to making sure you have a working solution.

A few years ago I worked on a project that involved a two stage migration for a membership organization with some 600,000 active contacts. Every one of them needed to be migrated into Salesforce and then into Drupal. To test the Drupal migration we needed samples of all the types of membership statuses we would see, which involved hand creating several hundred records. At the next Salesforce Commons Sprint I raised the idea of needing a better tool for this kind of work, that question eventually helped lead to Paul Prescod‘s creation of Snowfakery. Snowfakery will build you testing data sets of any size and complexity to make sure your processes will succeed.